Final project 2.2 Final Project

Project Title

Table of Contents

Introduction:

In this project, we discuss the impact of genetic variation on the use of CRISPR-Cas9 as a therapeutic tool. We first outline the difficulties of avoiding off-target effects in the use CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology, which is made more difficult by the unique SNPs in an individual’s personal genome. We next propose a tool to identify PAM sites in the reference genome as well as in Carl Zimmer’s genome and then compare the sets. Finally, we calculate libraries of guide RNAs for both genomes and discuss their differences.

Writing:

How might SNPs in Carl’s genome impact the use of CRISPR as a treatment? Discuss how individual SNPs would impact the off-target effects in the presence of the SNP.

CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases are gene-editing technology that can be used to cleave specific sites in the genome of a living cell. They are made up of two component parts: a Cas9 protein and a guide RNA (gRNA), also known as a single guide RNA (sgRNA), which is approximately 100 nucleotides in length. When used for genome editing, the CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease recognizes two sites on the target DNA: the protospacer and the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence. First, the Cas9 protein binds with the PAM site. Next, the 5’ end of the gRNA base-pairs with the protospacer, which is then cleaved.

CRISPR-Cas9 has many applications that involve specific genome editing. It has already been used in agricultural and research contexts, but arguably the most exciting application for CRISPR-Cas9 is to alleviate the effects of genetic disease. In the future, CRISPR-Cas9 could be used to correct disease-causing mutations in patients with cystic fibrosis, muscular dystrophy, or even cancer. However, CRISPR-Cas9 has not yet been proven safe enough for therapeutic use in humans, as it cannot yet be used with perfect accuracy.

A significant challenge to the use of CRISPR-Cas9 is the prevalence of off-target cleavage mutations. In theory, cleavage should only occur at sites with sequences that perfectly match both the protospacer and PAM sequence intended to bind to the gRNA and Cas9 protein, respectively. However, in practice, off-target sites with up to five mismatched nucleotides can also be cleaved by the CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease with similar efficiencies as the intended site. If enough off-target sites are cleaved, this could cause major structural effects in the genome, including deletions, translocations, and other rearrangements. For CRISPR-Cas9 to be used as a therapeutic tool, methods must be improved to computationally predict these off-target effects, detect them if they occur, and effectively prevent them.

Two potential methods of preventing off-target effects are to increase the specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases and to limit their activity overall. One method to increase CRISPR-Cas9 specificity is to use shorter gRNAs, with the intent that there will only be sufficient base-pairing to bind the gRNA to a given sequence if it is a perfect match. In order to limit the activity of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases, their half-life may be decreased with the intention of preventing binding to less likely sites.

Designing gRNAs is an important aspect of CRISPR-Cas9 efficacy. It is important to use gRNAs that have only one perfect match site in the genome, and most desirable to use gRNAs that also have no close matches in the genome.

Recently, software called GuideScan was developed in order to improve the selection of gRNAs (Perez et al. 2017). The software can be customized for a particular genome and Cas9 protein. The user then defines their desired PAM site, the distance between the PAM site and the protospacer, and the size of the gRNA. The software then provides sets of gRNAs that could be used to edit the genome in the desired fashion. Importantly, the software predicts gRNAs that would be prone to off-target effects and eliminates them. Generally, this includes gRNAs for which there are other sequences in the given genome that are an exact or close (by one or two nucleotides) match with the desired protospacer. In this way, GuideScan can be used to increase the specificity of gene-editing with the supplied gRNAs.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), which cause the genome of interest to differ from the reference genome at a particular point, can impact CRISPR-Cas9 efficacy in two ways. First, a SNP in the intended protospacer or PAM site could cause the CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease to cleave that site less efficiently or not at all. This is relatively easily avoided by specifically examining the sequence of the region of the genome where CRISPR-Cas9 is meant to bind and accounting for any SNPs that may be present.

Second, a SNP elsewhere in the genome that increases the similarity of that region to the intended site may introduce an off-target effect. In this case, examining the reference genome may not reveal any off-target sites, but the SNP may have allowed for an unpredictable off-target effect. This is more difficult to detect, because it involves examining a much larger portion of the genome – possibly the entire genome. However, the ability to predict which mismatched sequences or potential SNPs may increase the likelihood of off-target effects may help avoid this problem.

Doench et al. investigated the likelihood of specific sequences to cause off-target effects (2016). They found that off-target effects can result from slightly mismatched PAM sites or protospacer sequences. For example, a Cas9 protein that is targeted to a PAM site with the sequence NGG could show off-target activity at NAG, NCG, or NGA PAM sites.

Whether mismatched protospacer sequences result in CRISPR-Cas9 activity is heavily dependent on the position of the mismatch and the type of mismatch. For example, in the particular sequence investigated by Doench et al, an insertion or deletion relative to the intended protospacer rarely caused off-target effects, unless they occurred at positions 2, 3, 19, or 20 for insertions or positions 2 or 3 for deletions (2016). Note that in the case of an insertion or deletion relative to the intended protospacer, the DNA or gRNA will bulge outwards, respectively, upon binding.

Mismatched bases are more likely than insertions or deletions to lead to off-target effects. Again, the frequency of off-target effects depends heavily on the position and type of mismatch. For example, in the case studied by Doench et al, off-target activity would be likely to occur if a position occupied by a cytosine in the intended protospacer was replaced by a thymine. In contrast, off-target activity was unlikely if a position occupied by a guanine in the intended protospacer was replaced by a cytosine. Specifically at position 16, no off-target effects would occur if a protospacer pyrimidine was replaced with a purine, but off-target effects would occur if any other nucleotide were replaced with a thymine.

Considering this last example, it can be understood how individual SNPs may cause unpredicted off-target effects. If the intended protospacer had a cytosine at position 16, and another site in the reference genome was a match for the protospacer except for a guanine at position 16, no off-target effects would be predicted, and this site would not be considered a risk. However, if the individual had a SNP that replaced the position 16 guanine with a thymine, off-target effects would occur and could have a strong unintended effect.

These trends, therefore, can be used to predict the likelihood of off-target effects in the genome, particularly when SNPs are present that cause the individual genome to differ from the reference genome. These are important to consider, especially when CRISPR-Cas9 is being used on an individual genome, such as the Zimmerome.

Coding:

Here we present an implementation of a tool which finds PAM sites in the genome of subjectZ, the human reference genome, and compares the two sets.

The premise for this tool is as follows. Z’s genome has been aligned to refernce version 37, so we begin with aligned .fa files for both the Z and reference genome. We first search for the 5’-NGG-3’ motif across chromosomes in both genomes. We also search for the reverse complement 3’-CCN-5’. Our comparison of similarity is to find sites which are preserved between Z and the reference.

To determine sequence preservation, we had to extend our sequences. A 3-nucleotide region is too small to reliably detect, especially when one base in that motif is not constrained. To preserve functional specificity, we collect 21 nucleotides upstream of the 5’-GG-3’. We then take the first 1000 PAM sites per chromosome on the reference genome, find all PAM sites (with 21nt 5’ flank) on Z’s genome, and determine what fraction of sites were exactly preserved between the two. While CRISPR targeting does not require an exact match between gRNA and target, and in theory two PAM sites may be preserved if their flanking regions differ, this level of complexity was not possible to model without taking on a large number of additional assumptions (and increasing runtime).

Documentation

Please see the attached .Rmd file for code (also displayed below)

# load this package to help with parsing genome strings

library(Rsamtools)

# read in Z's genome

files <- paste0('~/Dropbox/Z_haplotype_1.fa')

PAM_sites <- list()

# parse Z's genome, find PAM sites with the GG motif, and store the adjacent 21 nucleotides

for (j in 1:length(files)){

file_path <- files[j]

indexFa(file_path)

x <- Biostrings::readDNAStringSet(file_path)

# as read in, the files have many regions which were not readable--many consequtive

# nucleotideas are marked N for unknown. This makes it difficult to find PAM sites

# with high confidence...

# to correct for this, each of our hits MUST have a GG in the last two positions

seqs <- function (df, chr){

buffer <- paste(rep("N",21), collapse="")

pattern <- paste(c(buffer,"GG"), collapse="")

chr1_PAM_GG <- matchPattern(pattern, df[[chr]], fixed=FALSE)

idx <- grepl("GG$", chr1_PAM_GG)

chr1_PAM_GG <- chr1_PAM_GG[idx,]

# we also look got CCN to find putative sites on the reverse strand

pattern <- paste(c("CC",buffer), collapse="")

chr1_PAM_CC <- matchPattern(pattern, df[[chr]], fixed=FALSE)

idx <- grepl("^CC", chr1_PAM_CC)

chr1_PAM_CC <- chr1_PAM_CC[idx,]

seqs <- list(chr1_PAM_GG, chr1_PAM_CC)

names(seqs) <- paste0(chr,c('_GG','_CC'))

return(seqs)

}

# add the names of the chromosome for sanity

for (i in (1:length(x)+(length(x)*(j-1)))){

chromosome <- names(x)[(i-((j-1)*length(x)))]

print(chromosome)

#PAM_sites[[i]] <- seqs(x, chromosome)

names(PAM_sites)[[i]] <- chromosome

}

}

# Store the output

Carl <- PAM_sites

# read in the reference genome

PAM_sites <- list()

ref_path <- '~/Downloads/GCF_000001405.25_GRCh37.p13_genomic.fna'

indexFa(ref_path)

x <- Biostrings::readDNAStringSet(ref_path)

# Find PAM sites in the reference and store the chromosome names

for (i in (1:length(x))){

chromosome <- names(x)[i]

print(chromosome)

PAM_sites[[i]] <- seqs(x, chromosome)

names(PAM_sites)[[i]] <- chromosome

}

# Filter out genomic regions which didn't map or aren't chromosomes

idx <- grepl('contig',names(PAM_sites))

Ref <- PAM_sites[!idx]

Ref <- Ref[1:24]

# Downsample the number of PAM sites

Csubset <- list()

Rsubset <- list()

for (i in 1:length(Ref)){

print(i)

idx <- which(end(Carl[[i]][[1]])<end(Ref[[i]][[1]][1000]))

tmp <- Carl[[i]][[1]][idx]

Csubset[[i]] <- unlist(lapply(tmp, toString))

}

for (i in 1:(length(Ref))){

print(i)

idx <- which(end(Ref[[i]][[1]])<end(Ref[[i]][[1]][1000]))

tmp <- Ref[[i]][[1]][idx]

Rsubset[[i]] <- unlist(lapply(tmp, toString))

}

# Calculate the relationship between Z and the reference

fractions <- vector(mode='double', length=length(Rsubset))

for (i in 1:length(fractions)){

print(i)

fractions[i] <- length(intersect(Csubset[[i]], Rsubset[[i]]))/length(Rsubset[[i]])

}

Results

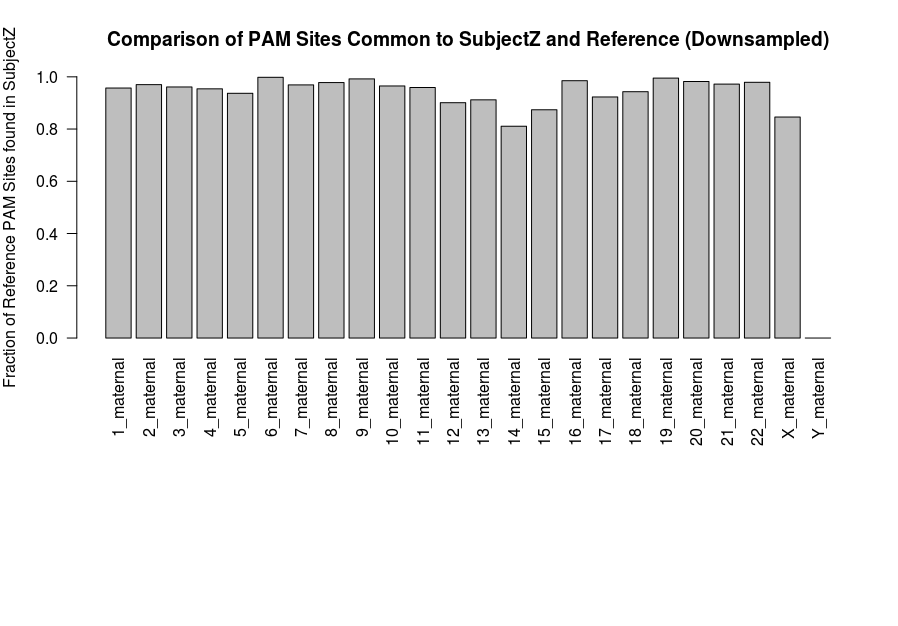

The following shows the similarity of Z’s genome to the reference for the first 1000 PAM sites on each chromosome. As expected, many sites are preserved. The variability observed here may be due to the effects of downsampling, which was necessary given memory constraints on this implementation.

# Plot the relationship between Z's PAM sites and those in the reference

par(mar=c(15,4,4,2))

fractions <- fractions[1:23]

names(fractions) <- names(Carl)[1:length(fractions)]

barplot(fractions, ylim = c(0,1), las=2, main = 'Comparison of PAM Sites Common to SubjectZ and Reference (Downsampled)', ylab='Fraction of Reference PAM Sites found in SubjectZ')

Pipeline:

sgRNA libraries for reference and Carl’s genomes.

Documentation:

GuideScan software is an open-source package (available at https://bitbucket.org/arp2012/guidescan_public/overview) that constructs gRNA libraries based on user-defined parameters (required dependencies for the software include python 2.7 with easy_install, along with rename, biopython, samtools, pyfaidx, and bx-python packages, and the pysam module - details can be found in the README.md file that comes with downloading the GuideScan software). In addition to generating libraries based on the most recent human reference genome, GRCh38, and those of other species, it allows users to input their own .fasta file, such as those of Carl Zimmer or GRCh37, which was used for the alignment of Carl’s reads. GuideScan allows users to input a list of chromosome names, desired gRNA length (excluding the PAM sequence and typically 20 to 100 bases long), alternative (to canonical NGG) PAM sites to analyze off targets (defalt is NAG). Users can also include a minimum mismatch similarity (M, default=2) between off target loci and a maximum off target genomic distance for more degenerate potential off-target loci (Q, default=3).

On interactive online version of GuideScan (www.guidescan.com) allows users to examine a much smaller guideRNA library with a user-friendly interface. The online tool is convenient when looking at a single specific guideRNA and information of its off-target loci. The typical output is an Excel file with the following columns:

- chromosome name/number (eg chr18)

- target site start coordinate

- target site end coordinate

- the guide RNA sequence

- cutting efficiency score

- cutting specificity score

- strand (+/-)

- number of total off targets found

-

off target summary (in the form of M:N_M Q:N_Q, where N_M and N_Q are the number of number of off targets with M and Q mismatches, respectively)

The cutting specificity and efficiency scores are based on Doench et. al. The specificity score is the likelihood a gRNA will be cut at each individual off target site. It is calculated by counting neighbors of up to Q mismatches, getting a cutting frequency determination (CFD) value and a count for each mismatch neighbors (that is, unique targetable sites in a user-specified range of mismatches) using a mutation matrix. The counts and corresponding CFDs are multiplied and the results are summed. The specificity score is the reciprocal of this value.

Results and Discussion:

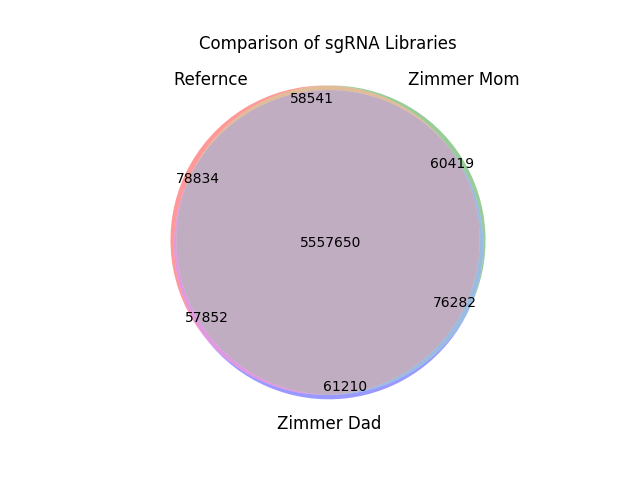

Using Carl’s maternal and paternal genomes and the GRCH37 reference genome, three sgRNA libraries have been constructed using the canonical PAM sequence NGG and a sequence length of 20 bases for chromosome 18. The maternal, paternal, and reference genomes each have 5.75 million sgRNAs, 5.56 million of which are common to all three libraries. The maternal library shared 97.93% of its entries with the paternal library, slightly higher then the 97.61% is shared with the reference genome. Only 1.05% of the maternal sgRNAs are unique to that genome. Similarly, only 1.06% of the paternal sgRNAs are unique to the paternal genome and 1.37% of the reference sgRNAs were not found in either the paternal or maternal genomes. The results are summarized in the venn diagram below:

Source code

References:

Barrangou R, Doudna JA. 2016. Applications of CRISPR technologies in research and beyond. Nature Biotechnology 34:933-941.

Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, Hegde M, Vaimberg EW, Donovan KF, Smith I, Tothova Z, Wilen C, Orchard R, Virgin HW, Listgarten J, Root DE. 2016. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nature Biotechnology 34:184-191.

Perez, AR, Pritykin Y, Vidigal JA, Chhangawala S, Zamparo L, Leslie CS, Ventura A. 2017. GuideScan software for improved single and paired CRISPR guide RNA design. Nature Biotechnology.

Tsai SQ, Joung JK. 2016. Defining and improving the genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases. Nature Reviews: Genetics 300-311.