Final project 2.1 Final Project

2.1 Identifying off target CRISPR sites

Table of Contents

Introduction: CRISPR/Cas in the Context of Genome Editing

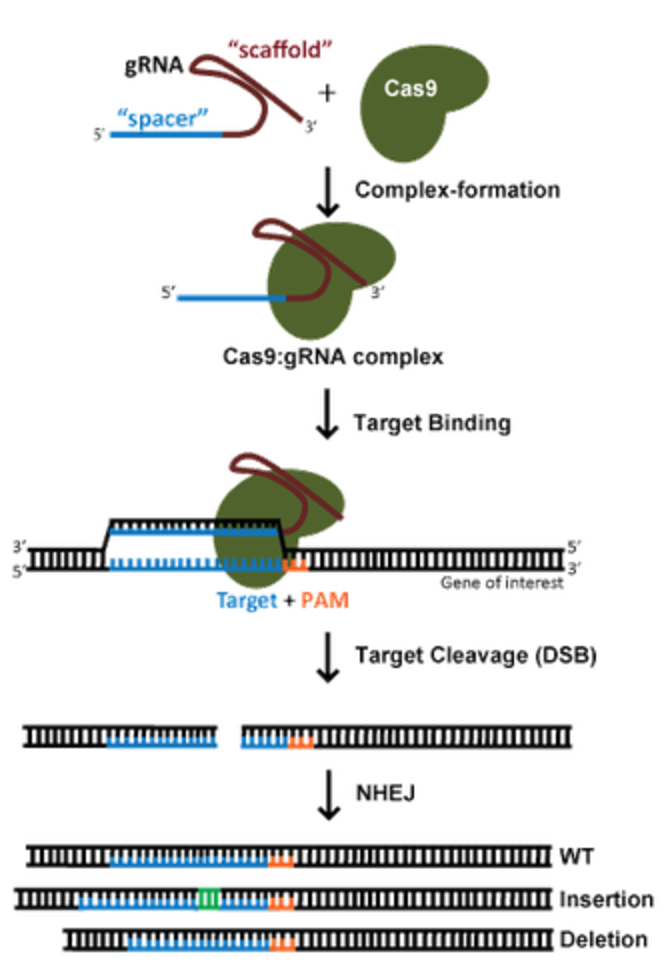

Since the discovery of its versatile genome editing function in 2013, the CRISPR/Cas system has been heavily studied for its use in targeted genome modification in eukaryotic cells. In many current applications, the Cas9 endonuclease from Streptococcus pyogenes is directed by a synthetic single stranded guide RNA (gRNA) containing homology to a genomic region. The gRNA displaces the duplex DNA and forms its own RNA:DNA duplex with one of the DNA strands. Cas9 then cleaves both strands of the DNA, inducing native DNA repair pathways. At this point, if random mutations at the site is the end goal, non-homologous end joining occurs with indels. However, if a specific point mutation or sequence insert is the goal, the addition of a double stranded DNA of interest will result in a small population of recombinants with the change after Cas9 action.

image from addgene.org

Writing:

Off-Target Effects and “Determinants of CRISPR/Cas sgRNA Specificity” (1)

The sheer size of the human genome often means that the gRNA target sequence is at least partially homologous to several locations in the genome. This binding of gRNAs to unintended genomic sequences is referred to as off-target effects. Even with the careful design of gRNAs, off-target binding is high and gRNA dependent – between 10-1300 off target binding events were observed in one study with 12 different gRNAs (2). Currently, off-target effects are one of the primary set backs for clinical application of CRISPR/Cas9. However, there are several mechanisms that confer specificity to the CRISPR/Cas9 system that can be leveraged to reduce off-target effects.

PAM site:

As shown in orange in the figure above, the protospacer adjacent motif, or PAM site, is a 3 base pair sequence expected to bind the 3’ end of the designed gRNA. It has been shown to be absolutely required in the genome to target Cas9, as it is at the 5’ end of the PAM site that Cas9 introduces a double stranded break into the DNA. About 50% of the time in humans, the PAM sequence is the GGG motif, though NGG is also seen (2). Depending on the origin species of the Cas9 employed, different PAM motifs can be probed.

gRNA & PAM Proximal versus PAM Distal

The gRNA consists of two main elements: a scaffolding piece to bind Cas9 and a target piece complementary to a region in the genome. The designed gRNA is often about 20 nucleotides long. While intuition suggests that longer sequences may confer higher specificity, this was proven wrong (1). Free single stranded RNA is highly unstable, and it is thought that Cas9 protects only about 20 nucleotides from degradation.

The PAM proximal region of gRNA is that which is closest to the PAM site while the PAM distal gRNA region is farther from the site. In a genome-wide ChIP-seq experiment using 12 gRNAs to characterize their off-target binding preferences, near-perfect homology of gRNA to DNA was observed at the PAM-proximal region (2). On the other hand, the PAM distal region had up to 10 mismatches with the genomic DNA (2). The PAM proximal region is referred to as the seed sequence to ensure gRNA specificity. The exact number of bases for this region is heavily debated but ranges between 1-12 nucleotides (1)(2)(3).

While the target sequence is very important, some studies have shown that the scaffolding piece of the gRNA is also critical. Both lengthening and shortening the 3’ end of the gRNA were shown to reduce gRNA expression (1). Still another group showed that lengthening the hairpin region tethering the gRNA to Cas9 can improve stability and target specificity of the complex (1).

The gRNA is the most important determinant of Cas9 specificity. The exact mechanism by which gRNA confers this specificity is not well understood. Some potential mechanisms include changing “the thermodynamic stability of the gRNA:DNA duplex,” the effective concentration of Cas9-gRNA (higher = less specific), the blocking of other Cas9 sites for trans-acting binding proteins, and the conformation of Cas9 to better access chromatin (1).

Chromatin Structure and Methylation:

DNA exists as tightly compacted coils around histone proteins in human cells, and this results in bulky, complex structures that can sometimes impede protein-DNA interactions. Thus, gRNA binding is heavily biased towards binding more accessible regions of the genome. One study showed that over 50% of gRNA binding is in open chromatin regions (2). Less accessible chromatin regions also correspond to higher epigenetic activity, namely CpG methylation. The presence of these marks has been suggested to block Cas9 binding (1)(3).

Cas9 related factors:

Because of the fast action of Cas9 and rapid degradation, the addition of purified Cas9 is reported to help reduce off-target effects (3). Furthermore, Cas9 can be modified into a nickase, such that it only cuts one DNA strand and a pair of gRNAs and nickases can be used for greater stringency (4).

The Inputs Required for Off-Target-Effect analysis of gRNAs

For off-target analysis, most tools simply require the gRNA sequence and a genome to search. gRNA specific parameters can either be inputs or set by the program such as tolerated mismatches, gRNA length, specific genome region, etc. Some tools also allow the specification of PAM site based on the Cas9 ortholog used. More advanced tools allow for the inclusion of ENCODE data, specifying chromatin structure across the genome to account for this as well.

Comparison of De novo tool and Other Prediction tools such as: CRISPR Seek and Cas OFFinder

For more detailed information about Jay’s tool and other prediction tools, see the Coding and Pipeline sections.

From my research, it appears that Jay’s tool shows more promise than Cas OFFfinder which Daniel used on a separate genome to test the tool’s ability to predict off-target binding sites. CasOFFinder only looks for PAM sequences and gRNA mismatches to PAM regions (5). There is no incorporation of PAM-proximal preference. One of the advantages of CasOFFinder is lower memory usage because it divides the genome into smaller chunks for searching and comparing (5).

CRISPR Seek does allow more user manipulation of the running parameters. Similar to defining the PAM-proximal regions as more important, CRISPR Seek allows the user to specify which nucleotides in the gRNA must be totally homologous to the genome (6). Furthermore, CRISPR Seek is compatible with Cas9 nickase experiments with 2 gRNAs and allows for optimization of such a system (6). However, when it comes time to pick off-target sites, again only mismatch number and PAM sequence parameters are used (6).

It is very difficult to include the full range of information discussed above into any one algorithm as what we know about the CRISPR/Cas9 system is always changing, and often does not hold true for all gRNAs. The next steps for Jay’s algorithm include the incorporation of ENCODE ChIP-seq data for chromatin structure, the weighted search of PAM sites accounting for their natural frequency, and Cas9 nickase experiment compatibility.

References:

- Wu, Xuebing, Andrea J. Kriz, and Phillip A. Sharp. “Target specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system.” Quantitative Biology 2.2 (2014): 59-70. Web.

- Kuscu, Cem, Sevki Arslan, Ritambhara Singh, Jeremy Thorpe, and Mazhar Adli. “Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease.” Nature Biotechnology32.7 (2014): 677-83. Web.

- Zhang, Xiao-Hui, Louis Y. Tee, Xiao-Gang Wang, Qun-Shan Huang, and Shi-Hua Yang. “Off-target Effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Genome Engineering.” Molecular Therapy - Nucleic Acids 4 (2015): n. pag. Web.

- “CRISPR/Cas9 Guide.” Addgene. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2017.

- Bae, S., J. Park, and J.-S. Kim. “Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases.” Bioinformatics 30.10 (2014): 1473-475. Web.

- Zhu, Lihua J., Benjamin R. Holmes, Neil Aronin, and Michael H. Brodsky. “CRISPRseek: A Bioconductor Package to Identify Target-Specific Guide RNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome-Editing Systems.” PLoS ONE 9.9 (2014): n. pag. Web.

Coding:

Documentation: De novo Off-Target Mutation Prediction Tool for SubjectZ

MAGE: Markov Affinity GRNA Extraction

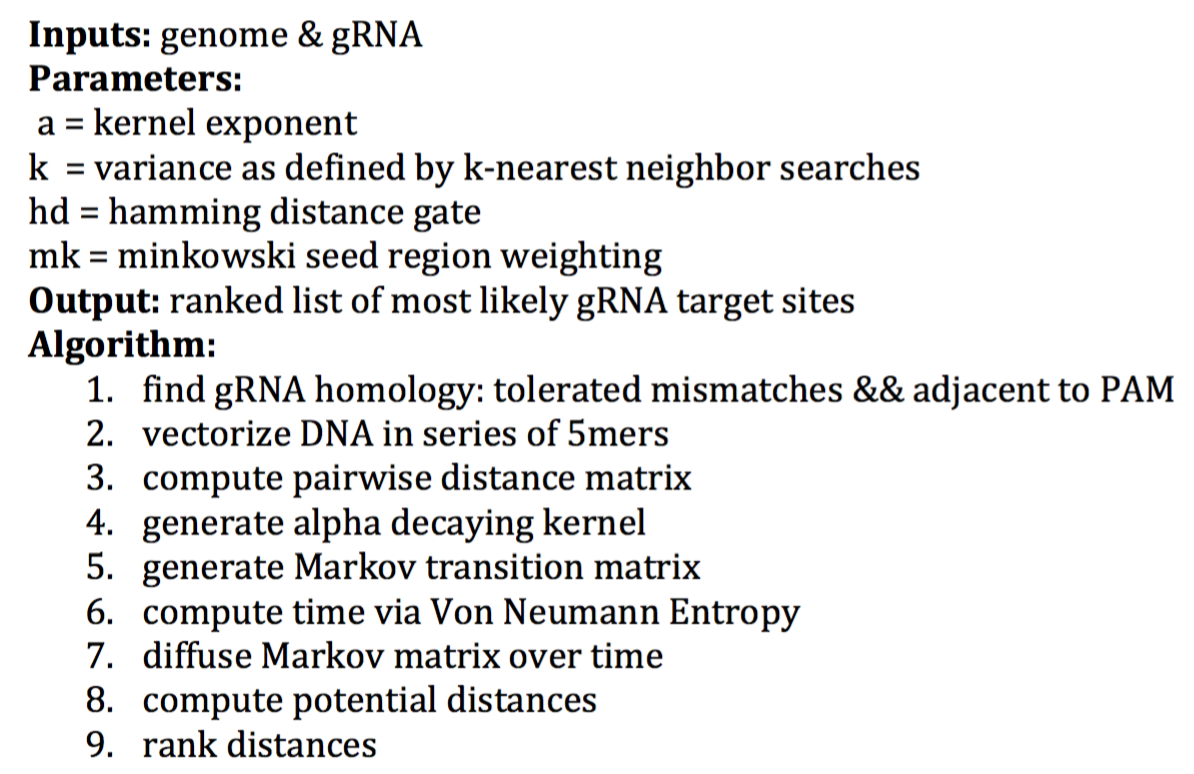

Amongst the literature concerning CRISPR/Cas off-targeting, few unifying themes have emerged: 1) CRISPR off targetting is primarily a function of sequence homology.

- Traditional alignment methods do not adequately predict the probability of offtargetting.

- Given a set of roughly similar 20-mers (as might be extracted from a naive search for off targets), alignments will not produce adequate dynamic range to quantify their differences.

- Similarly, more blunt statistics such as Hamming distances yield many false positives, as they are far too sensitive. 2) The degree of sequence homology required for binding varies based on proximity to the PAM sequence

From these insights, we assert that a new sequence similarity score is necessary to adequately measure guideRNA offtarget probabilities. Kernel methods lend themselves well as a tool to generate such similarities. MAGE is a parallelized diffusion-based method that operates on a candidate space of off target sequences, extracted using Hamming distance gating.

First, in order to generate a vector space to operate on, and to facilitate useage of kernels that are agnostic to the feature space, we map extracted possible off targets into a 500 dimensional space using DNA2Vec, a semantic similarity neural network inspired by Word2Vec (1). MAGE then uses an alpha-decaying kernel to map sequences into a similarity space.

The mapping of distances within the alpha-kernel is unique to MAGE; it uses a user specified Minkowski weighting function wherein the seed region of the guide is weighted by some integer more than the tail regions of the guide and candidate off targets. This emphasizes similarity near the PAM sequence, addressing point 2. One interesting feature of this weighting is that it is metric independent; different weights can be applied using different weight functions, and the weights can be applied to non-euclidean metrics such as cosine similarity.

The alpha decaying kernel behaves similarly to a Gaussian kernel, however, its decay is much sharper, owing to its powering. This alpha parameter can thus be tuned within the model (by command line specification) to alter the similarity scoring of off targets. The bandwidth of the kernel is adaptive k-nearest neighbors (the bandwidth for each point is set by the distance to its kth neighbor), with a slight tweak: because the coordinate space of DNA mappings is not unique (points in this space can be duplicate, owing to duplication in the genome), kth-neighbor distances will be 0 for some i, k in large off target libraries. Thus, MAGE uses an adapting adaptive bandwidth, wherein k is incremented until it reaches a non-duplicate kth nearest neighbor distance for duplicate points. This is a novel technique. In addition, users may specify their own k to tune the model, however it is sensitive to k near the size of the off target space and will tune accordingly.

To produce a Markov transition matrix, we normalize K by its rows, and this output corresponds to the probability of any sequence in the offtarget space moving to another sequence. In the light of guide RNAs, we are thus primarily concerned with two qualities of this space: 1) How does the similarity transition probabilities perform over infinite time?

- Rephrased, where does a random walk on the sequence space, starting at the guide RNA, land? 2) What qualities does the gRNA vector in this kernel exhibit? This is given by the 1st row/column of the kernel.

Many mathematical methods exist to perform such analyses on Markov transition matrices. MAGE uses diffusion, a class of methods based on powering the Markov matrix. A time step to power the markov matrix over is extracted by second derivative optimization of the time step versus the Von Neumann entropy of the Markov Matrix at that time step. This is performed via eigendecomposition of a symmetric conjugate affinity matrix whose powered eigenvalues correspond to the powered eigenvalues of the transition matrix. The Von Neumann entropy (VNE) is effectively a measure of the principal eigenvalues of the Markov matrix (2). Over long diffusive time, the eigenvalues reduce, and the number of principal eigenvectors follows. Thus by optimizing t/VNE, we yield a transition matrix with few principal eigenvectors, yet retains the dynamic range of the matrix while behaving similarly to the limit of the matrix as t goes to infinity. The VNE optimization is output from the model for model tuning, and optionally, users may specify their own t.

With this diffusion operator, we then convert it into a potential using a -log transformation (2). Subsequently, the potentials are converted into potential distances. We have thus approximated diffusion distances between sequences extracted from the genome. These distances are embedded using multidimensional-scaling. This output is a graphical representation of the diffusion probability between the target sequence and all of the other off target sequences in the genome.

Additional offtarget descriptors are produced using a feature-scaled potential distance matrix. The first vector of this matrix is the [0,1] scaled diffusion distance, which is mapped onto unit exponential and unit normal distributions to produce binding probabilities based on diffusion distance. These are output into a csv file, which is a universal format for exchanging table-based data.

Because the initial filtering of this tool is blunt (Hamming distances), the candidate space can be quite large; this yields computationally intensive matrix operations as well as less meaningful output for the user (as probabilities become more equivalent after normalization due to many components in the vector). Thus, the software offers the ability to screen out the lowest probability offtargets to reduce this load.

Because of the integrated Minkowski weights and the DNA2Vec representation of the candidate space, MAGE is amenable to future adaptations and modifications that append directly to the feature vectors. One such modification could be to include ENCODE data in the feature vectors.

A step-wise procedure for MAGE folllows:

References:

- Patrick Ng. “dna2vec: Consistent vector representations of variable-length k-mers”. arXiv preprint. arXiv:1701.06279 [q-bio.QM]

- Kevin R. Moon, David van Dijk, Zheng Wang, William Chen, Matthew J Hirn, Ronald R Coifman, Natalia B Ivanova, Guy Wolf, Smita Krishnaswamy. “PHATE: A Dimensionality Reduction Method for Visualizing Trajectory Structures in High-Dimensional Biological Data”. bioRxiv preprint. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/120378

Usage:

Dependencies: MAGE requires these packages: 1) Python 3.6 2) numpy 3) pandas 4) scikit-learn 5) scipy 6) Biopython 7) dna2vec (linked in this repository)

To use:

python3 ./stanley_2_1_2017.py -sgr <FASTA of SGRNA> -gnm <GENOME FASTA> -out <output dir>

The following parameters are used with MAGE:

-hd: hamming distance for candidate gating - default 5-mk: minkowski weighting integer - default 15-k: k nearest neighbor bandwidth - default 50-a: alpha of alpha decaying kernel - default 5-sd: second derivative minimum for VNE optimization - default 0.1-t: override VNE optimization with t - default 0-trange: Time steps to optimize over-mds: MDS embedding - default 0 (no embedding); 2 for nonmetric MDS (slower), 1 for metric mds-vne: plot VNE - default 0 (no plot)-num: amount of sample to include in output, default = num_candidates-cores: number of cores to use, default is 1, suggested is maxPipeline:

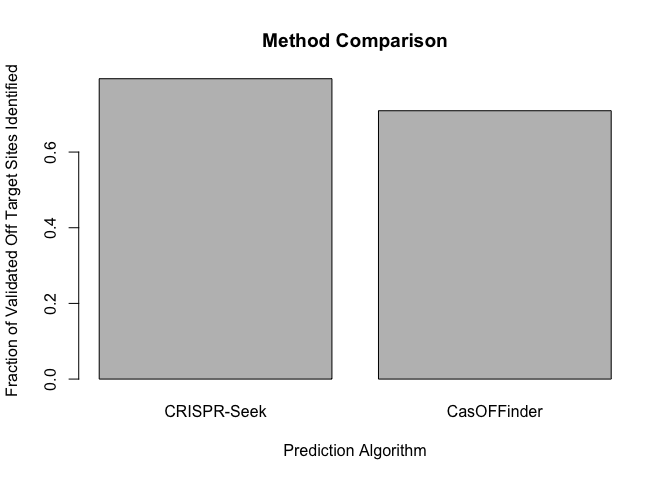

Here we examine the results of two CRISPR off-target prediction tools, CRISPR-Seek (Zhu et al 2014) and Cas OFFinder (Bae et al 2014). These methods were compared in Haeussler et al (2016). CRISPR Seek utilizes an empirically derived substitution matrix to score the likelihood that sites will be cleaved by the Cas9 nuclease given similarity to the guide (with the substitution matrix quantifying mismatch penalties). Cas OFFinder searches the genome for patterns indicative of PAM sites, and scores putative sites based on base mismatches against the guide query. The following analysis compares the performance of these methods against the human reference genome (build 38), and compare against the benchmarking results from Haussler et al (2016).

Documentation:

load libraries

library(tidyr)

library(dplyr)

##

## Attaching package: 'dplyr'

## The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

##

## filter, lag

## The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

##

## intersect, setdiff, setequal, union

library(reshape2)

##

## Attaching package: 'reshape2'

## The following object is masked from 'package:tidyr':

##

## smiths

library(CRISPRseek)

## Warning: package 'CRISPRseek' was built under R version 3.3.3

## Loading required package: BiocGenerics

## Loading required package: parallel

##

## Attaching package: 'BiocGenerics'

## The following objects are masked from 'package:parallel':

##

## clusterApply, clusterApplyLB, clusterCall, clusterEvalQ,

## clusterExport, clusterMap, parApply, parCapply, parLapply,

## parLapplyLB, parRapply, parSapply, parSapplyLB

## The following objects are masked from 'package:dplyr':

##

## combine, intersect, setdiff, union

## The following objects are masked from 'package:stats':

##

## IQR, mad, xtabs

## The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

##

## anyDuplicated, append, as.data.frame, cbind, colnames,

## do.call, duplicated, eval, evalq, Filter, Find, get, grep,

## grepl, intersect, is.unsorted, lapply, lengths, Map, mapply,

## match, mget, order, paste, pmax, pmax.int, pmin, pmin.int,

## Position, rank, rbind, Reduce, rownames, sapply, setdiff,

## sort, table, tapply, union, unique, unsplit, which, which.max,

## which.min

## Loading required package: Biostrings

## Loading required package: S4Vectors

## Warning: package 'S4Vectors' was built under R version 3.3.3

## Loading required package: stats4

##

## Attaching package: 'S4Vectors'

## The following objects are masked from 'package:dplyr':

##

## first, rename

## The following object is masked from 'package:tidyr':

##

## expand

## The following objects are masked from 'package:base':

##

## colMeans, colSums, expand.grid, rowMeans, rowSums

## Loading required package: IRanges

## Warning: package 'IRanges' was built under R version 3.3.3

##

## Attaching package: 'IRanges'

## The following objects are masked from 'package:dplyr':

##

## collapse, desc, regroup, slice

## Loading required package: XVector

## Warning: package 'XVector' was built under R version 3.3.3

library(BSgenome.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19)

## Loading required package: BSgenome

## Loading required package: GenomeInfoDb

## Loading required package: GenomicRanges

## Warning: package 'GenomicRanges' was built under R version 3.3.3

## Loading required package: rtracklayer

library(TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg19.knownGene)

## Loading required package: GenomicFeatures

## Warning: package 'GenomicFeatures' was built under R version 3.3.3

## Loading required package: AnnotationDbi

## Loading required package: Biobase

## Welcome to Bioconductor

##

## Vignettes contain introductory material; view with

## 'browseVignettes()'. To cite Bioconductor, see

## 'citation("Biobase")', and for packages 'citation("pkgname")'.

##

## Attaching package: 'AnnotationDbi'

## The following object is masked from 'package:dplyr':

##

## select

library(org.Hs.eg.db)

##

We began by pulling 31 guide RNAs and 650 experimentally validated off target sites from the supplemental data of Haussler et al (2016). The guides were then be fed into CRISPR-Seek and CasOFFinder to generate predicted off target sites. These predictions were compared against the validated set to assess each method’s performance.

# LOAD IN THE GUIDE RNAS AND VALIDATED OFF TARGET SITES FROM THE PAPER

df <- read.table('~/Downloads/13059_2016_1012_MOESM2_ESM.tsv', sep='\t', header=TRUE, stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

# there are 31 unique guide RNAs

# length(unique(df$guideSeq))

# 650 unique off targets

# length(unique(df$otSeq))

# extract guides and off target sequences

guides <- unlist(substr(unique(df$guideSeq),1,20))

offTarget <- unique(df[,c('guideSeq','otSeq')])

# write guide RNAs to file for usage in off target tools

seqNames <- 1:length(guides)

seqNames <- paste0('>', seqNames)

outFile <- paste(seqNames, guides, '', sep='\n')

write(outFile, '~/Desktop/gRNA.fasta')

Results:

Here we see that CRISPR-Seek predicts 496 sequences which are present in the validated dataset. Checking for the reverse compliment of CRISPR-Seek prediction increases this number to 516. ## CRISPR-Seek

# GENERATE LIST OF OFF TARGET SITES FROM CRISPRSEEK

# results <- offTargetAnalysis(inputFilePath = '~/Desktop/gRNA.fasta', findgRNAsWithREcutOnly = FALSE, findPairedgRNAOnly = FALSE, findgRNAs = FALSE, BSgenomeName = Hsapiens, txdb = TxDb.Hsapiens.UCSC.hg38.knownGene, orgAnn = org.Hs.egSYMBOL, max.mismatch = 4, outputDir = '~/Desktop/', overwrite = TRUE)

# READ IN RESULTS FROM CRISPRSEEK

CRISPRSEEK <- read.table('~/Desktop/OfftargetAnalysis.xls', sep='\t', header=TRUE, stringsAsFactors = FALSE)

list1 <- CRISPRSEEK[,c('OffTargetSequence')]

Rlist1 <- DNAStringSet(list1)

Rlist1 <- Biostrings::reverseComplement(Rlist1)

Rlist1 <- unlist(lapply(Rlist1,toString))

# Check the number of off targets predicted by CRISPR Seek that are in the validated dataset

sum(list1 %in% offTarget$otSeq)

## [1] 496

sum(list1 %in% offTarget$otSeq) + sum(Rlist1 %in% offTarget$otSeq)

## [1] 516

CasOFFinder predicts 461 of the 650 validated off target sites. ## CasOFFinder

# GENERATE LIST USING CASOFFINDER (www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder)

# this was done using their online tool because R integration is not supported

# READ IN CAS-OFFINDER results

CASOFF <- read.table('~/Dropbox/result.txt', sep='\t', header=FALSE)

CASOFF_offtargets <- toupper(CASOFF[,3])

RCASOFF_offtargets <- DNAStringSet(CASOFF_offtargets)

RCASOFF_offtargets <- Biostrings::reverseComplement(RCASOFF_offtargets)

RCASOFF_offtargets <- unlist(lapply(RCASOFF_offtargets,toString))

# Check the number of off targets predicted by CAS-OFFinder that are in the validated dataset

length(intersect(CASOFF_offtargets,offTarget$otSeq))

## [1] 441

length(intersect(RCASOFF_offtargets,offTarget$otSeq))+ length(intersect(CASOFF_offtargets,offTarget$otSeq))

## [1] 461

Comparison against published analyses

The authors of the multi-tool analysis report that CasOFFinder finds all

validated off target sites. Though we ran the tool with the same

tolerance of up to 4 mismatches, we did not recover all validated sites.

This may be because we ran our prediction against one version of the

genome, while the curated list of validated off-target sites come from

numerous genome versions across several studies. CRISPR-Seek does

slightly better with a total of 516 identified sites, but likely suffers

from the same limitation (though the authors do not explicitly test the

performance of this tool)

Conclusions:

Our pipeline shows similar performance of CRISPR-Seek and CasOFFinder in predicting validated off target sites from 31 guide RNAs. Discrepancies between our work and that published in Haeussler et al likely step from differences in target genomes.

Source code

References:

1.Zhu, L. J., Holmes, B. R., Aronin, N. & Brodsky, M. H. CRISPRseek: A Bioconductor Package to Identify Target-Specific Guide RNAs for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome-Editing Systems. PLoS One 9, (2014).

2.Bae, S., Park, J. & Kim, J.-S. Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics 30, 1473–1475 (2014).

3.Haeussler, M. et al. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 17, 148 (2016).