Final project 2.1 Final Project

Part 2.1 - Identifying Off-Target CRISPR Sites

Table of Contents

Introduction:

Background and Project Summary

Recently, RNA-guided endonucleases (RGENs) have been superseding traditional programmable nucleases like transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) and zinc-finger nucleases (ZFNs) as the genome editing nucleases of choice (Tsai & Joung, 2016). Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) RGENs consist of the Cas9 endonuclease derived from \textit{Streptococcus pyogenes} and single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that can be customized easily. Unlike TALENs and ZFNs, CRISPR RGENs can be manipulated in an easy and cost-efficient manner, which may account for its observed increase in use.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has huge implications in the treatment of genetic disorders. For example, gene editing using CRISPR RGENs has already precisely corrected genes related to Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy in patient induced pluripotent stem cells (Li et al, 2014). This finding goes to show that CRISPR-Cas9 can be used as a real therapeutic agent with further development.

At the same time, however, many scientists have cautioned against the direct therapeutic application of CRISPR-Cas9 to human patients. This concern is due to the nonspecific effects of CRISPR RGENs. Compared to the dimeric ZFNs and TALENs, monomeric CRISPR-Cas9 RGENs only recognize short sequences of 20 nucleotides, making it more prone mutate off-target sites, which can be detrimental (Zischewski et al., 2017). Therefore, when designing sgRNAs to knockout specific genes, it is important to take off-target effects into consideration and to document all potential off-target sites. (Ideally, we would like to minimize if not altogether eradicate the number of mutations at sites other than the gene of interest. We can minimize the off-target effects due to CRIPSR by using high quality sgRNAs.)

Thus, the goal of this project was two-fold. For one part, we used different off-target site prediction programs to look at and compare predicted off-target sites to the off-target site predictions proposed by CRISPOR given a specific guide RNA sequence. For the other part, we proposed a tool such that it takes in a given genome and guide RNA sequence and outputs potential off-target CRISPR sites.

Writing:

Background: How does CRISPR Work?

It may be helpful to first review how the CRISPR-Cas9 system works.

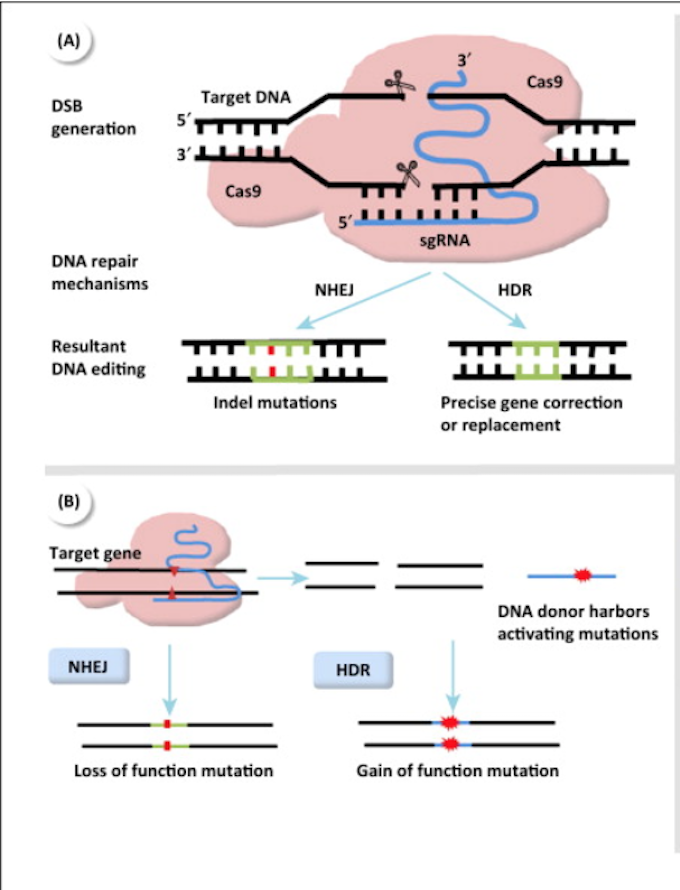

CRISPR-Cas9 was first characterized as an adaptive immune host defense found in the bacteria \textit{S. pyogenes}. In the native CRISPR-Cas9 system, there are three steps to achieving immunity against foreign DNA: (1) activation, (2) expression, and (3) interference (Pyne et al., 2016). In the first step, nucleotide tags of the exogenous genome called protospacers are rapidly acquired by the host genome and integrated into the CRISPR locus (the integrated protospacers in the host genome are referred to as spacers) (Pyne et al., 2016). The protospacers are flanked by a highly conserved sequence called the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) (Pyne et al., 2016). In the expression phase, these spacers are transcribed to pre-CRISPR RNA (pre-crRNA) and cleaved by the Cas9 endonuclease and a small transactivating RNA (tracrRNA) to form mature crRNA (Pyne et al., 2016). In the final stage, interference, the crRNA coupled with Cascade - a multiple-protein Cas complex - recognizes and binds to the complementary foreign DNA sequence (Pyne et al., 2016). Upon binding, Cas9 induces a double-strand break in the DNA duplex. The DNA must be rapidly repaired through one of two general mechanisms: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR) (Figure 1a). NHEJ is an imprecise DNA repair mechanism that can result in indels. This pathway is usually used more in CRISPR-Cas9-induced DSB repair. The other mechanism, HDR, when coupled with a donor template, can result in activating mutations through homologous recombination (Lu et al., 2015) (Figure 1b).

Essentially, application of the CRISPR-Cas9 system in other cells and organisms follows the same general mechanism outlined above. The only main difference is that the designed single guide RNAs (sgRNA) are comprised of \textit{fused} crRNA and tracrRNA (Pyne et al., 2016).

Figure 1: CRISPR Repair Mechanisms. Source: Lu et al, 2015.

Risk of Off-Target Mutations due to CRISPR

Because the sgRNAs used by CRISPR are short, the target sites are therefore short; there may be many sequences with high homology to the target site, resulting in more off-target mutations than other programmable nucleases (Tsai & Joung, 2016). Off-target mutations can range from being silent to being completely deleterious for cellular function. These detrimental effects can be felt in both the realms of wet lab research as well as clinical treatments.

For the former application, consider the case where scientists are attempting to determine the deletion phenotype associated with a specific gene. While the CRISPR-Cas9 system may seem like a good tool to use at first, unknown off-target mutations may confound the deletion phenotype; that is, a rare off-target mutation resulting in a marked phenotype may cause this phenotype to be ascribed to the target gene since this mutation was unknown. Thus, the risk of off-target mutations due to CRISPR in research is that experimental results may be misinterpreted.

For the latter, consider the situation that while CRISPR-Cas9 may target and silence a gene related to a specific disease of interest, off-target indel generation or homologous recombination leading to inactivation of tumor suppressor genes and/or inactivation of oncogenes can further result in tumorigenesis in the patient. Undesired cellular toxicity can also result from off-target effects (Ishida et al., 2015). Because CRISPR off-target effects can lead to such disastrous outcomes, this system remains unable to be applied in full-scale to human patients.

Factors that Determine the Likelihood of a CRISPR sgRNA Cutting at an Off-Target Site

The sgRNA itself determines the likelihood of off-target activity, and the key factor to CRISPR sgRNA binding to a DNA segment is sequence homology. Generally, off-target sites have high sequence homology with the desired target site (Tsai & Joung, 2016). While Cas9 can bind sequences with up to ten nucleotide mismatches, it can only cleave sequences with up to three to five nucleotide mismatches (Ishida et al., 2015).

While counter-intuitive, truncating the sgRNA length from the 5’ end actually increases specificity to the target site. Removing part of the sgRNA’s 5’ end decreases the excess potential energy ascribed to binding interactions at the DNA-RNA interface (Wu et al., 2015; Tsai & Joung, 2016). Due to this decreased potential energy, mismatches in off-target sites are less permitted, resulting in fewer off-target effects. Furthermore, an increase in the concentration of sgRNA/Cas9 complexes decreases the binding specificity (ie mismatches are more permissible), thus increasing the chance of off-target mutations (Wu et al., 2015).

While the PAM sequence - serving as a first recognition site of the sgRNA-Cas9 complex - usually has the conserved NGG sequence, non-canonical PAMs (such as NGA, NAG, and NTG) can also be recognized by the Cas9 endonuclease complex; off-targets with these PAM sequences can still be cleaved at a lower efficiency (Ishida et al., 2015). The PAM and the PAM adjacent sequence - the 20 nucleotides directly next to the PAM sequence - together are defined as the seed sequence. Cas9 scans the seed sequence from the PAM side (3’ end). Because of this scanning directionality, mismatches are less permissible in the seed sequence region. On the other hand, mismatches are more permissible in the non-seed sequence region (5’ end) (Ishida et al., 2015).

The effect of epigenetics is another important factor that should be taken into account for determining the likelihood of indel generation/homologous recombination at a specific site. That is, the DNA site must be accessible to the Cas9 endonuclease for it to be cut. Therefore, heterochromatin and methylated DNA result in a smaller chance of the Cas9-sgRNA complex cutting at those sites (Wu et al., 2015).

There are also lesser factors that only slightly impact the binding and cleavage of off-targets by Cas9. For example, it has been found that there is a preference for binding to sequences that contain a guanine rather than a cytosine as the nucleotide directly adjacent to the PAM sequence (Ishida et al., 2015).

Coding:

Documentation:

The proposed command line off-target site generation Python code finds potential off-target sites given a sgRNA and a genome.

The user inputs the genome as well as the sgRNAs in text file formats. The user can also set the maximum number of mismatches; here, the default is five mismatches, the maximum number of mismatches found in off-target sites proposed by literature (Tsai & Joung, 2016).

The program scans the DNA text file for designated PAM sequences (where the default PAM sequence is NGG); for each sgRNA within the text file, when the program finds a PAM sequence, it aligns the sgRNA with the 20 nucleotide PAM adjacent sequence using the Smith-Waterman algorithm (match score of 1, mismatch score of 0, initial gap penalty of 1, and gap extension penalty of 10). The perfect alignment of sgRNA to the inputted genome is considered the on-target site.

A neat feature of this program is that it also checks the reverse complement to see if the sgRNA will bind with the other strand (which is a possibility, especially in high concentrations of the sgRNA/Cas9 complex).

Results:

An example DNA sequence (a subset of a genome) and sgRNA sequences (seen below) were entered into the program.

The example DNA sequence is given by:

ACCGTACAAGCGTTCCGCATTAATTGTCAGCCGGCGCCACGCAATGGAACATCCTTAACTCCGGCAGGCAATTAATGGGAACGTATGTATAACTTTGCGTTATACATACGTTCCCTTTAATTGCCTGCCGGAGTTAAGGACGTTCCATTGCGTGGCGCCGGGTGCAAA

And the three sgRNA are as follows:

CGTTCCCTTTAATTGCCTGC; and

ACGTTCCATTGCGTGGCGCC.

Both sgRNAs yielded an on-target site and two off-target sites (one on forward strand, one on reverse strand) in the output. The resulting output file can be found in Katya’s gRNAtargets.txt file in the Crispr_2.1 folder.

Pipeline:

An Introduction: Off-Target Site Prediction Programs

The two off-target site prediction programs used in this project - in addition to CRISPOR - were (1) ChopChop and (2) COSMID.

ChopChop is an online tool that offers selections of sgRNA based on versatile searches from long target regions and predicts off-target effects given sgRNAs (Montague et al., 2014). COSMID is also an online tool that is able to predict off-target sites and to output optimal amplification primers for the chosen application for given sgRNA, PAM sequence, and number of mismatches (Cradick et al., 2014).

Documentation:

The data for CRISPOR was taken directly from the paper source (Haeussler et al., 2016).

The analyses were run with the software ChopChop and COSMID and the off-target site predictions were summarized in the Excel file final_crispr.xlsx. The results for each prediction program are cataloged by three different tabs in the Excel worksheet. The final tab - otSites (short for off-target sites) - summarizes a comparison of the three different software. The total number of off-targets, average residuals, and percent error compared to CRISPOR are listed at the bottom of the sheet. For ChopChop, two average residuals are listed, one with the maxed-out results and one without (boxed). The total number of off-targets and percent error do not include the maxed-out results. CRISPOR and ChopChop also provided rankings of the guide sequence.

Results:

Overall, CRISPOR provides the most information of the three techniques and also the highest off-target site totals. COSMID underestimates the number of double and triple mismatch off-target sites, but it seems to find significantly more single mismatches than either CRISPOR or ChopChop. This may be due to the fact that COSMID counts mismatches in the PAM sequence as well, which the other two tools do not do. Furthermore, COSMID provides the least amount of information about the sgRNA sequence, providing only the off-target sequence, chromosome position, and a score. It also does not allow for batch submissions, which makes comparison between sgRNA sequences difficult. However, COSMID does allow for off-target sites with indels, while CRISPOR and ChopChop do not (though the creators of CRISPOR argue that indels/bulges are rare causes of off-target sites).

CRISPOR chose Hsu_EMX1.6 with a guide specificity score of 88 and ChopChop chose Hsu_EMX1.1 as its top-ranked guide sequence. Furthermore, the disparity with CRISPOR is the worst for both ChopChop and COSMID when finding three-mismatch off-target sites.

Conclusions:

In this project, we reviewed the current online tools and proposed a program for identifying off-target effects due to the CRIPSR/Cas-9 system. From the example input text files, Katya demonstrated that her program does indeed output the correct matches for both on- and off-target sites, thus highlighting the fact that her tool can accurately predict off-target sites. For the pipeline portion, Krystle showed that out of the three off-target prediction programs compared, CRISPOR is the most helpful in terms of providing the most informative output.

This project gave a glimpse into the complex problem now facing scientists and clinicians alike in determining sgRNAs for implementation with the CRISPR-Cas9 system. These insights on off-target sites can lead to the selection of high-quality sgRNAs with fewer off-target effects. Hopefully, with the identification of sgRNAs that are only specific to the designated target sequences, the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be used more prevalently in both research and clinical settings.

Source code

References:

Cradick, T.J., Qiu, P., Lee, C.M., Fine, E.J. and Bao, G., 2014. COSMID: a web-based tool for identifying and validating CRISPR/Cas off-target sites. Molecular Therapy—Nucleic Acids, 3(12), p.e214.

Fu, Y., Foden, J.A., Khayter, C., Maeder, M.L., Reyon, D., Joung, J.K. and Sander, J.D., 2013. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nature biotechnology, 31(9), pp.822-826.

Haeussler, M., Schönig, K., Eckert, H., Eschstruth, A., Mianné, J., Renaud, J.B., Schneider-Maunoury, S., Shkumatava, A., Teboul, L., Kent, J. and Joly, J.S., 2016. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biology, 17(1), p.148.

Ishida, K., Gee, P. and Hotta, A., 2015. Minimizing off-target mutagenesis risks caused by programmable nucleases. International journal of molecular sciences, 16(10), pp.24751-24771.

Li, H.L., Fujimoto, N., Sasakawa, N., Shirai, S., Ohkame, T., Sakuma, T., Tanaka, M., Amano, N., Watanabe, A., Sakurai, H. and Yamamoto, T., 2015. Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem cell reports, 4(1), pp.143-154.

Lu, X.J., Qi, X., Zheng, D.H. and Ji, L.J., 2015. Modeling cancer processes with CRISPR-Cas9. Trends in biotechnology, 33(6), pp.317-319.

Montague, T.G., Cruz, J.M., Gagnon, J.A., Church, G.M. and Valen, E., 2014. CHOPCHOP: a CRISPR/Cas9 and TALEN web tool for genome editing. Nucleic acids research, 42(W1), pp.W401-W407.

Pyne, M.E., Bruder, M.R., Moo-Young, M., Chung, D.A. and Chou, C.P., 2016. Harnessing heterologous and endogenous CRISPR-Cas machineries for efficient markerless genome editing in Clostridium. Scientific reports, 6.

Tsai, S.Q. and Joung, J.K., 2016. Defining and improving the genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases. Nature Reviews Genetics, 17(5), pp.300-312.

Wu, X., Kriz, A.J. and Sharp, P.A., 2014. Target specificity of the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Quantitative biology, 2(2), pp.59-70.

Zhang, X.H., Tee, L.Y., Wang, X.G., Huang, Q.S. and Yang, S.H., 2015. Off-target effects in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome engineering. Molecular Therapy-Nucleic Acids, 4, p.e264.

Zischewski, J., Fischer, R. and Bortesi, L., 2016. Detection of on-target and off-target mutations generated by CRISPR/Cas9 and other sequence-specific nucleases. Biotechnology Advances.