Final project 1.3 Final Project

Project 1.3: Analyzing the Protein Coding Mutations in the Zimmerome

Table of Contents

Introduction: What is Variant Prioritization?

Since the advent of rapid and cheap whole genome sequencing technologies, we have amassed a large and diverse collection of human genomes. Interpreting this large amount of data is still challenging, and one such challenge is understanding the function of single nucleotide variations (SNVs). These often arise in individual genomes compared to reference sets which also include many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Specifically, identifying pathogenic or deleterious mutations compared to common harmless mutations is a key challenge. Often, deleterious mutations are nonsynonymous, meaning that they result in the change of one amino acid to another. The average individual has over 10 million SNPs in the whole genome, about 20,000 of which are in the exome, or the protein-coding portion of the genome. Of course, not all of these are deleterious - the number of potentially deleterious mutations in the exome often amounts to about several hundred (1)(2). This problem of identifying relevant disease-causing mutations or variants compared to common mutations is called variant prioritization.

Here, we aim to prioritize variants in the exome of SubjectZ. SubjectZ has 22,981 exome SNVs of which 1,800 are rare SNVs (4). Furthermore, of these rare SNVs, 1,018 were found to be nonsynonymous. Both a de novo approach and existing tools such as SIFT, PolyPhen, and Provean will be used to perform variant prioritization. The methodology used to prioritize SNVs in the de novo tool will be explained and compared to those used in other approaches. The results of our tool and those from the mentioned tools are detailed in the Pipeline and Coding sections of this text.

Writing:

The Inputs Required for Variant Prioritization Tools

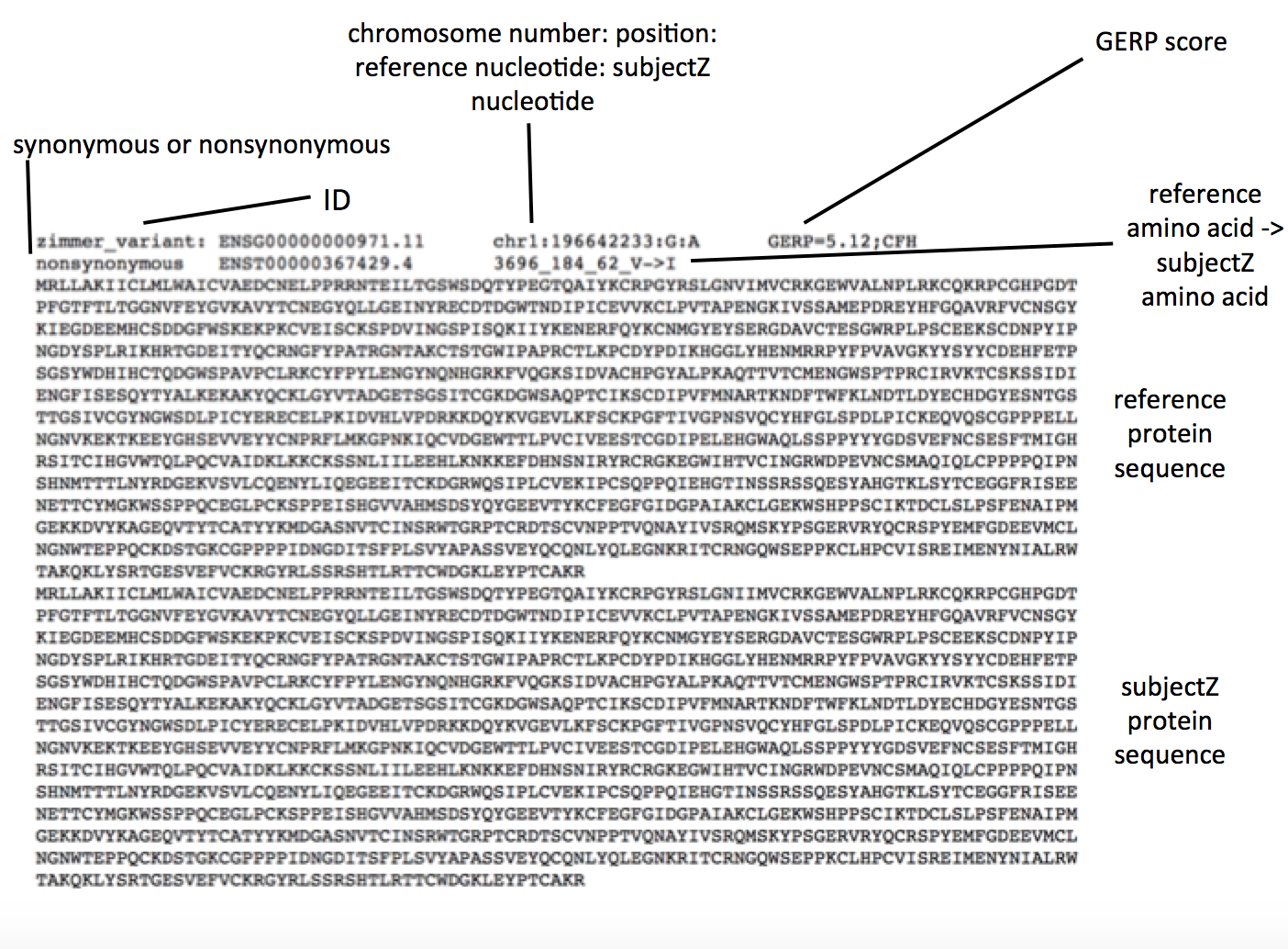

The output of an alignment of one individual’s genome to a reference is often a Variant Call Format file. This file contains not only information about mutations in the nucleotide sequence compared to the reference, but also important metadata regarding the quality of the alignment, and other important properties that can allow for further sub-classification (3). In our analysis, we have a paired down VCF text file containing the following information.

Perhaps the only non-self explanatory field is the GERP score which “measures evolutionary conservation of genetic sequence across species” (5). A higher score means that the nucleotide sequence is more conserved and variation is rarer and potentially more adverse. All of this information is parsed for prioritization.

Principles for Variant Prioritization

Ideally, variant prioritization employs several orthogonal pieces of data to effectively classify SNVs. I will discuss some commonly used parameters in variant prioritization and their significance.

Sequence Information:

Obviously, the nucleotide sequence information is used, namely to assess any mutations in amino acid. Synonymous mutations as mentioned are often harmless as they result in the same amino acid at the position. However, codon frequency can sometimes cause problems if the new codon does not have enough corresponding charged tRNAs for effective protein synthesis. Nonsynonymous mutations become more harmful as the amino acid substituted is more divergent in size and charge.

Conservation and Position:

Considering the conservation and position of SNVs is also important. Mutations in the hydrophobic core are often rarer, as these regions tend to be more well-conserved. A common hypothesis is that mutating conserved regions has a greater risk of deleteriousness. The reason rare SNVs are more likely to be deleterious is because other similar mutations have been eradicated from the population due to intolerance – probably because the mutation was in a well-conserved region and caused protein expression to fail in some way. Using structure prediction software such as TMHMM and Phyre2 to see whether the mutated amino acid is in a conserved internal secondary structure, active site, or membrane could give further insight into the effect size of the mutation (7).

This does not exclude common variants from the search as there are many examples of more common variants that influence well-known diseases such as breast cancer. The GERP score can be used to evaluate conservation in the case of SubjectZ. Looking at the amino acid level, a BLOSUM matrix accounting for the high degree of similarity between reference and subjectZ can be used to evaluate conservation.

Phenotypic Information and Prior Knowledge:

Existing information about the mutation can be accessed such as any existing information regarding the SNVs involvement in characterized diseases. This phenotypic information can be mined using the position of the SNV and/or the provided protein sequences. For example, finding the BRCA SNV alone (which occurs in about 3% of the population on average) may not have given it as high a priority as other rare SNVs, but armed with existing information about its critical role in breast cancer would lead to higher prioritization. Gene Ontology terms are good starting points for this type of information as well as SWISS-PROT entries. Considering whether the SNV was previously identified in the 1000 Genome project or in the dsSNPs database and checking these entries might provide further insights into the disease model of the mutation.

Other genetic factors:

All humans have two alleles of a given gene. Most often, only when both alleles are mutated (i.e. when the individual is homozygous for the mutation) does the disease phenotype arise. In some cases haploinsufficiency may arise, when the individual does have one functioning copy but it is not producing enough gene product for normal function. Checking whether the SNV identified is in only one or both alleles can help prioritize the mutation. Lastly, any co-varying mutations will not be caught by standard SNV ranking pipelines - only monogenic variants can be identified.

Ideally, gene information, variant information such as GERP scores, and phenotype information if any can be compiled and used with machine learning for optimal results (6)(7).

Comparison of de novo Tool and Common Variant Prioritization Tools like SIFT, PolyPhen2 and PROVEAN

For more detailed documentation of Nir’s tool and common variant prioritization tools, see the Coding and Pipeline sections.

Both SIFT and PROVEAN only take into account sequence information when calculating variant deleteriousness. PolyPhen2 is a much more advanced and nuanced tool, looking at sequence, structure, and existing functional information to make its prediction (8). It also resulted in no “undetermined” SNVs. Interestingly, although there were no synonymous SNVs in the input file, all open-source tools predicted a handful, possibly because the reference genomes the tools compare to are different from the one in the input file.

Nir’s tool does not look at existing functional information, but it does try to incorporate some amount of structural information by looking at size via molecular weight. Adding in a TMHMM search to rank membrane bound residues would probably help acheive better predictions. As an advantage, Nir’s tool considers both conservation at the amino acid level and the nucleotide level through the BLOSUM score and GERP score respectively.

Gerstein lab data shows that SubjectZ has 824 rare nonsynonymous coding variants (4). Given that we started from a file of about 3500 nonsynonymous SNVs and SubjectZ is supposed to contain over 10,000 nonsynonymous SNVs, it is unclear how our results (described below) compare to this data (4).

References:

- 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010 Oct 28;467(7319):1061-73. PubMed PMID: 20981092

- “What are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)? - Genetics Home Reference.” U.S. National Library of Medicine. National Institutes of Health, n.d. Web. 09 May 2017.

-

“IGSR: The International Genome Sample Resource.” VCF (Variant Call Format) version 4.0 1000 Genomes. N.p., n.d. Web. 09 May 2017. - http://archive.gersteinlab.org/proj/zimmerome/part05/ppt/Slides.coding_DC.pdf

- Cooper, Gregory M., Eric A. Stone, George Asimenos, Eric D. Green, Serafim Batzoglou, and Arend Sidow. “Distribution and intensity of constraint in mammalian genomic sequence.” Genome Research. Cold Spring Harbor Lab, 01 Jan. 1970. Web. 09 May 2017.

- Moreau, Yves. Variant Prioritization By Genomic Data Fusion. University of Leuven, Belgium, n.d. Web. 9 May 2017. pdf presentation

- Ng, Pauline C., and Steven Henikoff. “Predicting the Effects of Amino Acid Substitutions on Protein Function.” Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 7.1 (2006): 61-80. Web.

- “Overview.” Overview[PolyPhen-2 Wiki]. N.p., 10 Mar. 2017. Web. 09 May 2017.

Coding:

Documentation: De novo Variant Prioritization Tool for SubjectZ

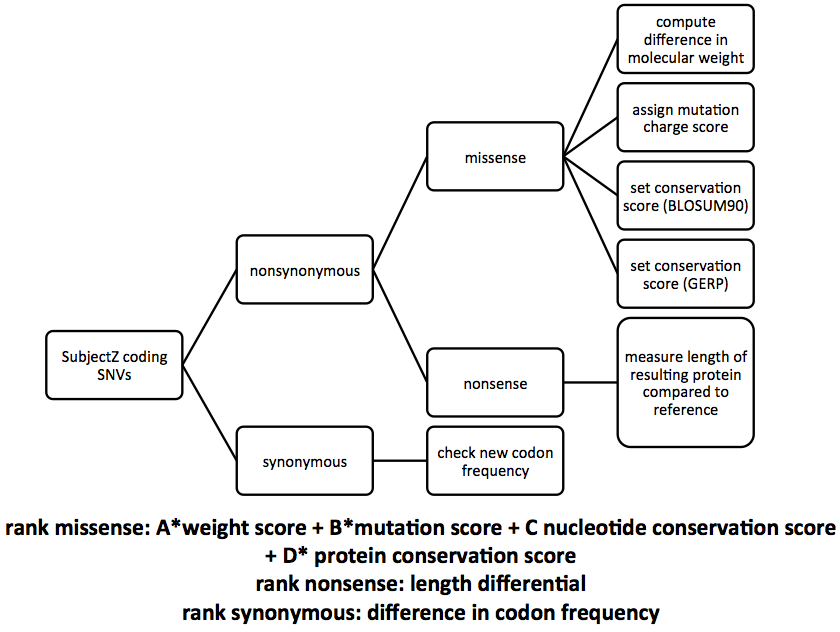

Below is an overview of the Variant Prioritization Tool constructed by Nir.

The first step is to parse the SNV file for SubjectZ that was provided. Next, simply by reading the the file, one can classify each SNV as either synonymous or nonsynonymous. This file only contains nonsynonymous mutations, so this step is skipped. If synonymous mutations did exist, the frequency of occurance of the new codon can be calculated and scored. Next the amino acid mutation must be characterized as either missense or nonsense. If it is a nonsense mutation, the algorithm compares the length of SubjectZ’s protein to that of the reference, classifying a larger difference in length as more deleterious. In the case of missense mutations, four parameters whose weights the user can decide are calculated. The size of the protein substitution is accounted for by calculating the difference in molecular weights, again with larger differences prioritized higher. The amino acid and nucleotide conservation scores are included through the BLOSUM and GERP scores for each substitution. Finally, a charge score, checking if the amino acid has changed properties or remained the same (neutral, hydrophobic, or hydrophillic) is included. Each of these four scores is added together with the user specified weights, generating a rank ordered list of SubjectZ’s SNVs.

The weights for each property of the missense mutation are left to the user because there is no consensus on what property is most important for determining deleteriousness. Several parameter combinations can be attempted and all results compared.

Results:

Pipeline:

Documentation

(Additional data files containing graphs and charts are separately uploaded and linked below)

The ability to predict harmful protein coding mutants is becoming increasingly important in both the clinical and the research setting, and as a result there have been many algorithms developed that predict whether a particular nucleotide change is harmful or not.

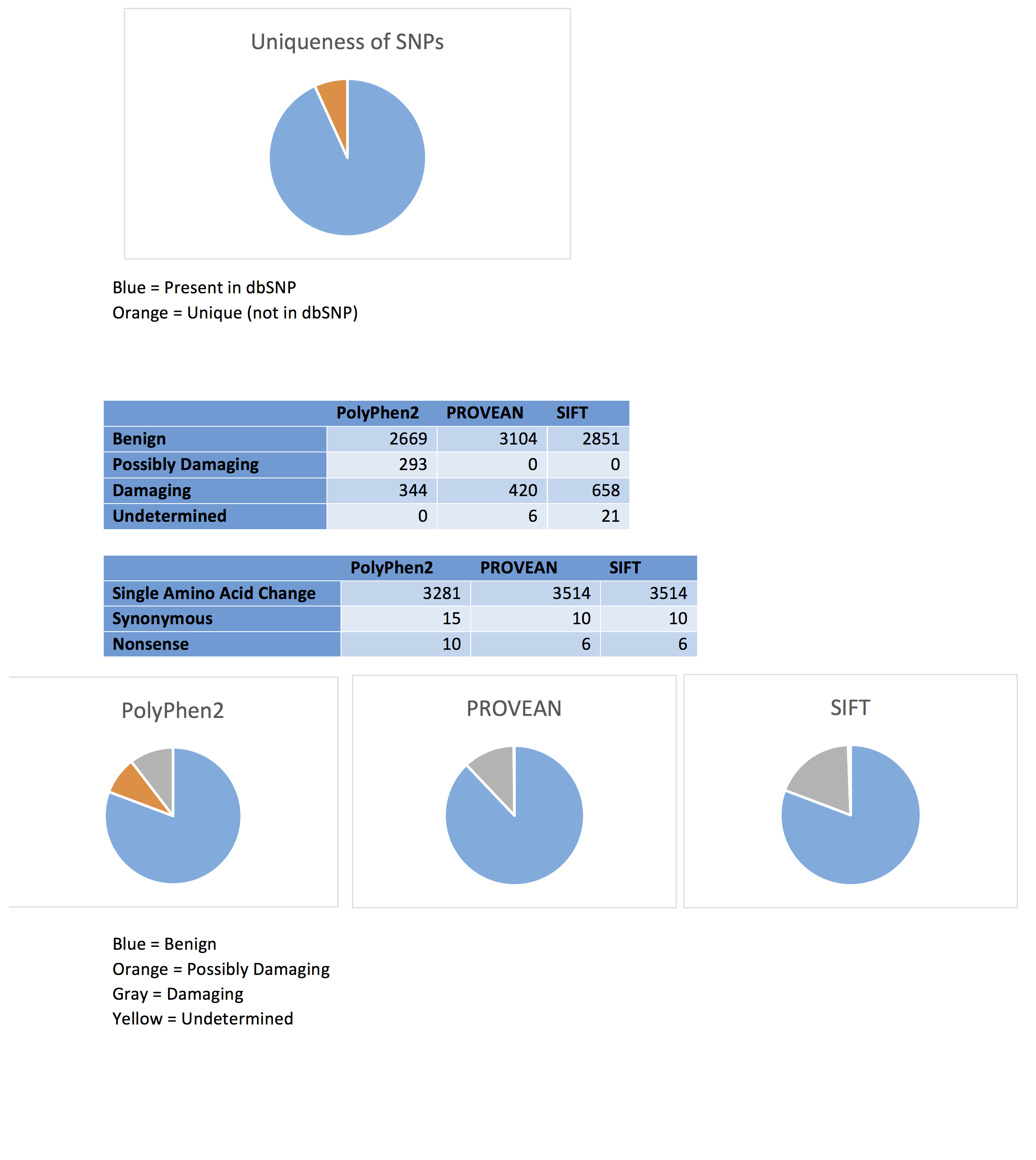

Many SNPs are quite common within a population. The output of PROVEAN, one of the programs used to analyze the deleteriousness of a particular variation, provides information on whether the individual SNPs are found within the SNP database or if they are a unique variant. Of the 3530 protein coding SNPs analyzed, 93.2% (3290) were present in the dbSNP, while only 6.8% (240) were unique mutations.

Some of the SNPs present in the VCF file are isoforms of the same protein. In the case where each isoform has the same mutation, it will likely have the same effect and classification (due to the similarity between the proteins). However, some cases may have different mutations in each isoform, with different classifications for the different variations. In either case, the presence of non-mutated isoforms or isoforms with benign mutations could have the ability to compensate for any function lost by a damaging variant. This complicates deleteriousness predictions, as it is possible that mutations classified as harmful, which likely have greatly altered structure and function, may not actually be deleterious overall, as the isoform with a proper structure can carry out the required functions.

PolyPhen2

The program PolyPhen2 was used to analyze Carl’s SNPs. This program calculates the probability that a particular SNP is “damaging”, using a Bayes classifier and information about the particular sequence, its conservation, and the structure of the gene (Adzhubei et al. 2013). The only input required is the chromosome number, the location of the gene within the chromosome, and the original and variant nucleotide. 3306 of the 3533 protein coding SNPs were analyzed using this method, with 89 of the original SNPs classified as belonging to introns, 17 to the 3’ UTR, and 11 to the 5’ UTR. Of the protein coding variants, 80.7% (2669) were classified as “benign”, with probabilities of being damaging ranging from 0 to .451. 10.4% (344) of the SNPs were predicted to be “probably damaging”, with a probability ranging from .959 to 1. SNPs were also classified as “possibly damaging”; 8.9% (293) of these fell into this category, with probabilities ranging from .454 to .948.

A ranking of the deleteriousness of the different SNPs was also created using PolyPhen2. The ranking is from a PolyPhen score of 1 (a very probable damaging mutation) to 0 (indicating a benign mutation). This can be compared to the ranking obtained through the other programs or through the program created, and can asses how closely these programs can classify and rank the different SNPs.

PROVEAN

The algorithm PROVEAN, assigns the SNPs as either “neutral” or “deleterious” through alignment base scoring (Choi and Chan, 2015). Of the 3533 SNPs input into the program, 3 were determined to be in a non-protein coding region, and were not analyzed further. The remaining 3530 protein coding SNPs were analyzed using this program. 87.9% (3104) were classified as neutral, with 11.9% (420) classified as deleterious. A further 0.2% (6) were unable to be classified. Of the neutral variations, 99.7% were single amino acid changes, while 0.3% were synonymous mutations. All of the deleterious mutations involved single amino acid changes, while all of the undetermined variants encoded nonsense mutations.

SIFT

The program SIFT was also used to analyze the 3530 protein coding SNPs (3 of the original 3533 were also found to be in non-protein coding regions). It uses sequence alignment and conservation to determine the probability of a particular mutation occurring, classifying a mutation as “damaging” if this value is below a particular cutoff (Kumar et al. 2009). 80.8% (2851) were considered to be “tolerated”, while 18.6% (658) were considered to be “damaging”. A further 0.6% (21) were undetermined. This program also gave an identical prediction with regards to the nonsynonymous and synonymous classification of the tolerated and damaging SNPs. Likewise, 6 variants classified as “undetermined” were considered to be nonsense mutations, the exact number as was found using PROVEAN.

Results and Conclusion

Each of the programs was fairly consistent in their classification of a particular SNP as benign or neutral. PolyPhen2 and SIFT had nearly identical classification into this category (80.8% vs 80.7%), while PROVEAN predicted slightly more neutral variants (87.9%). The three-category classification used in PolyPhen2 meant that fewer variants were predicted to be damaging, with 10.4% compared to the 11.9% and 18.6% seen with PROVEAN and SIFT respectively. Due to the very similar probabilities, SIFT likely classifies the “possibly damaging” mutants seen with PolyPhen2 as “damaging”.

Both PROVEAN and SIFT identified the same number of nonsynonymous, synonymous, and nonsense mutations. This implies that these algorithms can correctly classify the type of mutation, and that both programs have the ability to correctly recognize the codons within the genes and whether the mutation affects the amino acid being encoded. PolyPhen2 has similar results, with slightly fewer synonymous mutations and nonsense mutations detected. The similarity between these programs with regards to codon detection and deleteriousness predictions suggests that though the different algorithms classify the majority of SNPs in a similar way, there are still some variants which are variably classified. Experimental analysis through mutagenesis will be helpful in determining whether these variably classified SNPs are truly harmful or benign.

Source code

References:

Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting Functional Effect of Human Missense Mutations Using PolyPhen-2. Current protocols in human genetics / editorial board, Jonathan L Haines . [et al]. 2013;0 7:Unit7.20. doi:10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76.

Choi Y., Chan A.P. PROVEAN web server: a tool to predict the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(16):2745-2747.

Kumar P., Henikoff S., Ng P.C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nature Protocols. 2009;4(8):1073-1082.