Final project 1.1 Final project

Part 1.1 - Comparative Analysis of Personal Genomes

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

With the completion of the Human Genome Project, scientists have made great progress in cataloging the breadth of human genetic variation. Large-scale reference data for genetic variation plays a crucial role for the clinical interpretation of sequenced DNA variants. In recent years, such data has been used to inform and validate pathogenicity metrics for various classes of mutations. These advancements may soon allow for the widespread use of comparative analyses in interpreting personal genomes. In this project, we have developed tools to use reference datasets to find information on individual variants in Carl’s personal genome.

2. Writing

2.1 Instructions

Describe the 1000 Genomes and gnomAD databases and what can be learned from collections of variants observed in large populations. How have these databases evolved over the past decade?

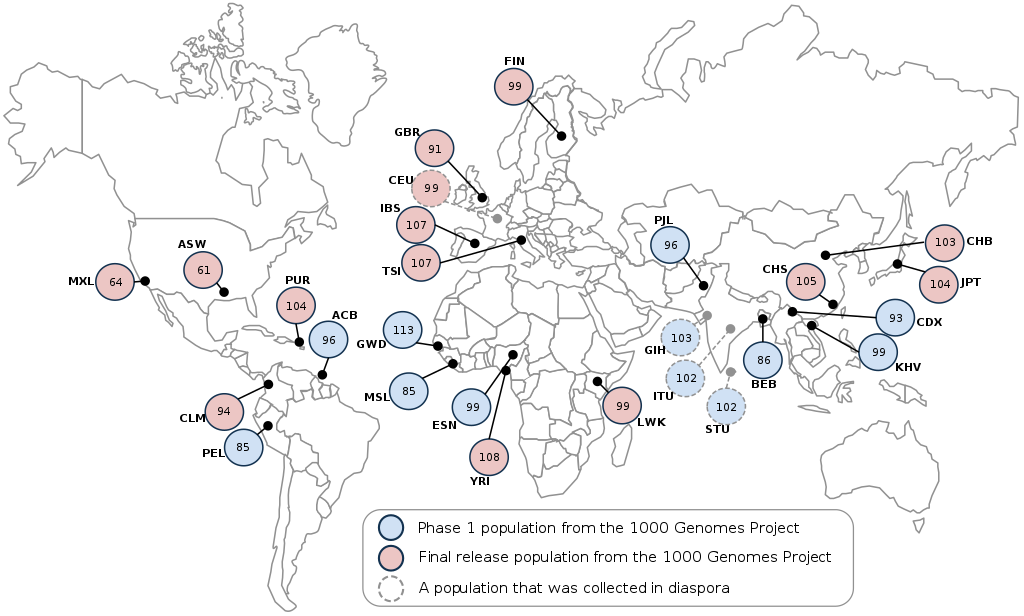

2.2 1000 Genomes Project

The 1000 Genomes Project was an international effort to sequence, for the first time, a large and diverse collection of human genomes (at least 1000). By the end of the 3 project phases, the consortium had sequenced 2,504 genomes from 26 global populations, including African, Admixed American, European, East Asian, and South Asian. With this many sequences, researchers were able to discover >95% of variants with minor allele frequencies higher than 1% (0.1-0.5% in gene regions). Additioanlly, it was found that, on average, each person carries 200-300 loss-of-function variants in annotated genes, and 50-100 variants (previously) implicated in inherited disorders. Although newer datasets contain many times more individuals, the 1000 Genomes Project remains a useful and high-quality dataset for population-level genome analysis.

Figure 1: Sample locations for the 1000 Genomes Project

2.3 Genome Aggregation Database

The Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) is an expansion from the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), developed by the MacArthur Lab at the Broad Institute. gnomAD seeks to aggregate germ-line exome sequences from a large number of sources (including the 1000 Genomes Project, among many others). It does this by uniformly processing and filtering exomes from these different studies. The result is 138,632 exomes across major continental populations, 15,496 of which are whole genomes. gnomAD provides a high-resolution picture of human genetic variation, allowing the analysis of very rare variants that had previously been undetected. So far, researchers have identified almost 18 million variants in gnomAD exomes and 254 million in gnomAD genomes, including 7.5 million and 160 million that were previously unknown in coding and noncoding sequences, respectively.

Table 1: Populations represented in gnomAD

| Population | Exomes | Genomes | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| African/African American (AFR) | 7,652 | 4,368 | 12,020 |

| Latino (AMR) | 16,791 | 419 | 17,210 |

| Ashkenazi Jewish (ASJ) | 4,925 | 151 | 5,076 |

| East Asian (EAS) | 8,624 | 811 | 9,435 |

| Finnish (FIN) | 11,150 | 1,747 | 12,897 |

| Non-Finnish European (NFE) | 55,860 | 7,509 | 63,369 |

| South Asian (SAS) | 15,391 | 0 | 15,391 |

| Other (OTH) | 2,743 | 491 | 3,234 |

| Total | 123,136 | 15,496 | 138,632 |

2.4 Applications to Personal Genome Analysis

Much can be learned from collections of variants in large populations. The first such dataset (1000 Genomes) enabled estimation of the rate of de novo germline mutation, as well as the average number of each mutation class (truncation, loss-of-function, etc.) carried by each individual. Newer datasets have additionally enabled the identification of novel variants, accurate estimation of allele frequencies, and stratification by ancestral population groups.

The clinical utility of carefully cataloging genetic diversity is clear. Analysis of a personal genome involves evaluating its differences from the normal range of genetic variation. This normal range is inferred by comparison to many other genomes in some database. A variant identified as disease-causing or protein-knockout can be searched up in such a database to find how common it is. Variants that are very common (relative to disease prevalence) may be dismissed as uninformative. Rare variants, on the other hand, are often considered to be highly penetrant.

2.5 Evolution of Genomic Databases

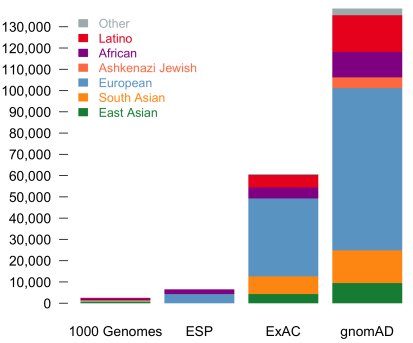

There have been three main areas of progress in genomic databases over the past decade: sample size, variant filtration, and data aggregation.

Sample size: The rise of next-generation sequencing has enabled the collection of massive amounts of data. Rapid improvements to efficiency, speed, and cost have increased the number of sequenced genomes and exomes documented in public databases. This has allowed unprecedented resolution for estimating allele frequencies, as well as identifying new variants.

Figure 2: Increased sample sizes in large-scale genomic databases

Variant filtration: Sequencing errors and mapping artifacts increase false positives. Variant filtration strategies are still evolving, but techniques such as Variant Quality Score Recalibration (VQSR) have adopted machine learning techniques to integrate information from multiple QC metrics to identify true variants. Scientists are capable of confident SNP-calling, but further improvements can still be made for calling indels and structural variants, particularly in low-complexity regions.

Data aggregation: Combining data across a large number of studies is an efficient way to increase the sample size of a genomic database. However, uniform processing and other corrections are needed to account for issues like variable coverage and reference bias. Groups like the MacArthur Lab, which assembled the ExAC and gnomAD databases, have developed a number of techniques for effectively managing and processing exome data in the past few years. In the future, efforts of similar methods and scale could be performed for genomes as well.

3. Coding

3.1 Instructions:

Propose a tool that finds information on a subset of Carl’s variants in the gnomAD and 1000 genomes databases.

3.2 Documentation:

Online browser and API access are not straightforward for users interested in using their own variant call files (VCFs) to retrieve a slice from a very large database. We propose a tool, vcfR, to help users to use VCFs to query certain variants within a reference dataset. The reference can be a standalone file or a link. The reference can be customized and the searching process is fast given proper reference and sorted order of query by genome position.

The usage of vcfR is as follows: python vcfR.py -i <input.vcf> -f <ref.vcf.gz> -o <output.vcf>

The matched terms in input file will be output to a file named input_matched.file in case of the comparison between matches and output. As mentioned earlier, vcfR can also deal with online reference, e.g., to query chr1 variants in 1000 Genomes and gnomAD:

Query gnomAD chr1

$ python vcfR.py -i sample_input.vcf -f

https://storage.googleapis.com/gnomad-public/release-170228/vcf/

genomes/gnomad.genomes.r2.0.1.sites.1.vcf.gz -o sample_out.vcf

Query 1000 Genomes chr1 phase 1

$ python vcfR.py -i sample_input.vcf -f

ftp://ftp.1000genomes.ebi.ac.uk/vol1/ftp/phase1/analysis_results/

integrated_call_sets/ALL.chr1.integrated_phase1_v3.20101123.

snps_indels_svs.genotypes.vcf.gz -o sample_out.vcf

3.3 Results:

File “sample_input.vcf” records a subset of objectZ’s variants (874 terms in total) in chromosome 1. We can use it as query to search matched information in databases. Here, we will show an example using vcfR.py to look for matches in gnomAD. The output files should be self-explanatory but sometimes users may also want to get annotations after the query. In this example, we will use ‘–anno’ option to get annotations for matched terms. All the annotations will be saved into a json file named “sample_input_matched.json”.

$ python vcfR.py -i sample_input.vcf -f

https://storage.googleapis.com/gnomad-public/release-170228/vcf/

genomes/gnomad.genomes.r2.0.1.sites.1.vcf.gz -o sample_out.vcf --anno

It would be easy to use tools or simple codes dealing with JSON files to get annotations. In this case, 854 variants are matched in gnomAD. Users are able to retrieve information after simple processing of the JSON file, for example, 190 variants in coding region are identified and the type of sequence variants is recorded, for example, chr1:g.12783G>A : intron_variant, chr1:g.14464A>T : non_coding_transcript_exon_variant…

Details for each entry are be found in the Coding files. The Python ‘json’ package is recommended for further analysis.

4. Pipeline

4.1 Instructions:

Identify and run a tool that finds the population frequencies for each of the variants observed in Carl’s genome and also look to see how many are private variants. How do these numbers change based on the two databases used?

4.2 Documentation:

To annotate large number of available NGS data, there is a large number of SNPs annotation tools available. Some of them are specific to some specific SNPs annotation. Some of the available SNPs annotation tools are: SNPeff, VEP, ANNOVAR, FATHMM, PhD-SNP, PolyPhen-2, SuSPect, F-SNP, AnnTools, SeattleSeq, SNPit, SCAN, Snap, SNPs&GO, LS-SNP, Snat, TREAT, TRAMS, Maviant, MutationTaster, SNPdat, Snpranker, NGS-SNP, SVA, VARIANT, SIFT, PhD-SNP and FAST-SNP.

4.2.1 ANNOVAR

We decided to work with ANNOVAR. This tool is suitable for pinpointing a small subset of functionally important variants. Uses mutation prediction approach for annotation. An important and probably highly desirable feature is that ANNOVAR can help identify subsets of variants based on comparison to other variant databases, for example, variants annotated in dbSNP or variants annotated in 1000 Genome Project. The exact variant, with same start and end positions, and with same observed alleles, will be identified.

Variant calling, made by the Gerstein Lab located 3,559,138 SNPs and 789,969 indels. Using ANNOVAR, we performed a comparison against 1000genome (version 1000g2015aug) and gnomAD (both in build hg19).

4.2.2 Sample Command Lines

Download relevant databases:

annotate_variation.pl -downdb 1000g2015aug humandb -buildver hg19annotate_variation.pl -buildver hg19 -downdb -webfrom annovar gnomad_genome humandb/

VCF conversion:convert2annovar.pl -format vcf4 -withfreq data/indel.vcf > data/indel.avinputconvert2annovar.pl -format vcf4 -withfreq data/snp.vcf > data/snp.avinput

Analysis:annotate_variation.pl -filter -dbtype 1000g2015aug_all -buildver

hg19 -out indel data/indel.avinput humandb/annotate_variation.pl -filter -dbtype hg19_gnomad_genome -buildver

hg19 -out snp.gad data/snp.avinput humandb/

4.3 Results:

Allele frequencies were collected variants in both 1000 Genomes and in gnomAD.

Table 2: Three examples from chromosome 1 in 1000 Genomes:

| Location | Reference | Alternate | Minor Allele Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 49554 | A | G | 0.063099 |

| 49298 | T | C | 0.782149 |

| 54490 | G | A | 0.096046 |

Table 3: Three different examples from chromosome 1 in gnomAD:

| Location | Reference | Alternate | Minor Allele Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10144 | T | C | 0.0007 |

| 92004 | A | G | 0.0387 |

| 108310 | T | C | 0.2959 |

A comparison of subjectZ (Carl) with all individuals in 1000 Genomes: 95% of the SNPs (~3.4M) and 60% of the indels (469K) were found in at least 1 other individual. This leaves 5% of the SNPs (~178K) and 40% of the indels (320K) as private variants.

A comparison of subjectZ with all individuals in gnomAD: 97.5% of the SNPs (~3.5M) and 90% of the indels (709K) were found in at least 1 other individual. This leaves 2.5% of the SNPs (~82K) and 10% of the indels (81K) as private variants.

Table 4: Known and unknown variants in the 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP) and gnomAD

| Source | 1KGP known variants | 1KGP unknown variants | gnomAD known variants | gnomAD unknown variants | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indel | 469,754 | 320,215 | 709,146 | 80,823 | 789,969 |

| SNP | 3,381,358 | 177,780 | 3,476,922 | 82,216 | 3,559,138 |

As we can see above, the proportion of private variants is different by 2.5% and 30% for SNPs and indels, respectively, when comparing 1000genome to gnomAD. gnomAD contains much more variants, as we expect, since it comes from a much larger cohort.

5. Conclusions

A comparative analysis of Carl’s personal genome is useful for finding which variants are functionally important, and how common those variants are. Here, we have developed tools and a pipeline for retrieving information on Carl’s personal variants. Although the variants were too numerous to collect annotations on all of them in our time frame, we demonstrate that, based on the gnomAD dataset, 2.5% of Carl’s SNPs and 10% of his indels are private variants. Additionally, our pipeline is able to collect allele frequency data for non-private variants. From here, it would not be a difficult next step to identify pathogenic annotations of shared variants as candidates for clinical reporting.

Source code

6. References

- The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68-74. doi:10.1038/nature15393.

- Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Samocha KE, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. bioRxiv. 2016;536(7616):30338. doi:10.1101/030338.

- Ashley EA. Towards precision medicine. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(9):507-522. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.86.

- Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional annotation of genetic variants from next-generation sequencing data, Nucleic Acids Research, 38:e164, 2010

- Oleksyk TK, Brukhin V, O’Brien SJ. The Genome Russia project: closing the largest remaining omission on the world Genome map. GigaScience. 2015;4:53. doi:10.1186/s13742-015-0095-0.